Police Career Center

Policing can be a fulfilling career that offers secure employment with advancement potential. Though opportunities for moving up the career ladder are strongly related to the size of the agency, all police departments have promotional systems in place that allow for the advancement of qualified candidates based on their work history, testing, and interviews. From local police departments and sheriff’s departments to state police and federal law enforcement agencies, policing follows a competitive promotion structure that offers a wide array of opportunities both in supervisory positions and in specialized duties, such as SWAT or K9 units.

Those best suited for a career in law enforcement are good listeners, excellent communicators, critical thinkers, perceptive of their surroundings, have sound decision-making skills, and are able to work well under pressure and with others. This guide will introduce readers to the typical progression through the ranks of sworn personnel (personnel who are authorized to make arrests, to carry firearms, and to use reasonable force when necessary) in law enforcement agencies, focusing primarily on municipal police departments and county sheriffs’ offices.

Table of Contents

- Entry-Level Law Enforcement Careers

- Organizational Structure

- The Promotions Process

- Mid-Level Ranks

- Higher Ranks

- Police Officer Salary and Career Outlook

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Additional Resources

Entry-Level Law Enforcement Careers

Everyone has to start somewhere, and careers in policing are no exception. The field of law enforcement offers many types of jobs, from entry-level patrol jobs to chief of police and sheriff’s positions. At the entry level, the title that those seeking police careers will use depends on the agency for which they work. In police departments, the entry level is police officer, whereas in sheriff’s departments, the entry level is typically deputy sheriff. State highway patrol officers start out as state troopers. Some federal agencies also hire federal police, such as the Commerce Department, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Department of Defense, and the National Park Service.

The following are job descriptions of various police officer jobs that may be available to those entering the field.

Police Job Satisfaction

“A look inside the nation’s police departments reveals that most officers are satisfied with their department as a place to work and remain strongly committed to making their agency successful.” -Pew Research Center, Behind the Badge

Police Officer

Following successful completion of the hiring process and graduation from the police academy, virtually all new police officers will begin their careers in the patrol division. Patrol officers are often called the “backbone” of the police department and comprise nearly two out of three sworn officers in some big-city agencies.1 Being a police patrol officer is arguably one of the most complicated jobs in the law enforcement arena because officers must deal with human beings in a seemingly infinite number of possible situations, often when people are at their worst. On any given shift, an officer will perform multiple roles: law enforcer, psychologist, referee, social worker, teacher, and crime fighter, just to name a few. An exhaustive list of a patrol officer’s tasks is nearly impossible to put on paper, but an officer’s responsibilities almost always include:

- Random vehicular, bicycle, or foot patrol of an assigned sector or “beat” for the purpose of deterring or displacing crime, making citizens feel safer, and allowing for quick response to calls for service.

- Directed patrol of “hot spots,” areas where a disproportionate amount of crime occurs.

- Responding to 9-1-1 and non-emergency calls for service which include criminal and non-criminal matters.

- Preliminary investigations of crimes including taking control of crime scenes, identifying evidence, and conducting initial interviews with victims, witnesses, and suspects.

- Officer-initiated response to and reporting of suspicious behavior.

- Conducting security surveys of businesses and/or residences as assigned for the purpose of crime prevention.

- Coordinating neighborhood watch meetings or attending other community forums.

- Traffic and crowd control at non-police emergency scenes; assistance of firefighters and/or emergency medical personnel.

- Enforcing traffic laws and responding to traffic incidents.

- Writing field activity and offense reports.

- Testifying in court about previous incidents.

- Providing escorts for funerals and other processions.

- Other duties as assigned.

Generally speaking, police try to respond to all calls and either handle the matters in question or refer the parties involved to someone else who can help them. The motto “to protect and to serve” that is emblazoned on many police vehicles results in a long list of duties from trivial and monotonous to dangerous and life-threatening. For this reason, police work can be extremely complex, so officers benefit from education, training, and on-the-job experience.

It is important to note that officers spend a great deal of time driving around waiting – for a call or for something to happen. Report writing and other administrative duties also consume a lot of time. Police work is often described as “hour upon hour of pure boredom interspersed with a few seconds of sheer terror.”2 While this is a hyperbolic statement, it is important to understand that the portrayal of policing in movies and television may not be realistic. Bona fide crime-fighting duties are relatively rare, and officers often spend more time serving people than they spend protecting them.

After gaining experience in patrol, officers may become eligible to transfer into special units such as K9, SWAT, and search and rescue. Transfers to special units are usually based on a combination of qualifications (including education and experience) and a promotional exam. However, while moving to a special unit is generally viewed as a promotion, those working on special teams do not “outrank” patrol officers in the majority of departments, except in the sense that they may have specific jurisdiction or control over certain types of active crime scenes and investigations that patrol officers typically do not. In some cases, these positions may come with higher pay and/or hazard pay.

Deputy Sheriff

Deputies in county sheriffs’ offices are roughly equivalent to patrol officers in city police departments. Although their geographical jurisdiction is different, taking on law enforcement at the county level rather than the city level, they are full-fledged peace officers who must meet similar standards as city officers. Their job descriptions are fundamentally the same, and with rare exceptions, the progression through the ranks is similar.

One significant difference is that in addition to their law enforcement duties, deputy sheriffs are responsible for incarcerating convicted as well as accused offenders who are awaiting trial, so the sheriff must assign some employees to jail duty. As a general rule, these correctional positions are held by civilians, but commissioned deputies do work as jailers in some agencies. Where jailers are civilian employees rather than deputies, these positions can provide a foot in the door for individuals who aspire to become deputies. In fact, some sheriff’s offices require prospective deputies to begin on the correctional side of operations. Some deputies start out in other non-sworn positions, such as dispatchers. Some very large sheriff’s departments may have specialty units such as SWAT and search and rescue (SAR).

State Trooper

State police troopers have a broader geographical jurisdiction than city police officers and county sheriffs’ deputies, as they operate at the state level, but their duties are similar. They may focus on traffic enforcement but are still commissioned peace officers who provide comprehensive law enforcement services. This frequently includes providing security for important monuments within the state, as well as for important state officials.

In some states, patrol and investigations are broken out into separate divisions. For instance, the Texas Department of Public Safety has a Highway Patrol Division that is responsible for traffic and criminal law enforcement in rural areas and on state highways and the Texas Rangers Division (the oldest state police agency in the US) to handle criminal investigations.3 There can be variation in rank structures and career progression in state police agencies, but as with departments at the county and city levels, they are hierarchical quasi-military organizations with time-in-rank promotional schemes that are very similar to those discussed below.

Federal Police

The federal government has a number of law enforcement agencies, some of which employ sworn police. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, about 7% – or 56,490 – of the police and detectives working in the US are employed by federal agencies.5 Note that this excludes officers with law enforcement authority working in capacities that do not have local police equivalents, such as special agents.

In addition to the suit-and-tie investigators that Hollywood often romanticizes, many federal agencies employ uniformed police officers (e.g., the Border Patrol and the Capitol Police). Federal agencies have somewhat limited jurisdiction. They are generally responsible only for federal laws and the protection of federal employees and property, and each agency handles cases that are unique to its mission. As such, the work of federal police officers is highly specialized.

The Secret Service, for instance, has a Uniformed Division that works to protect facilities and venues as well as the White House Complex, the Treasury Department building, and other security-sensitive properties. Interestingly, the US Postal Inspection Service, the law enforcement arm of the US Postal Service, which investigates mail fraud and crimes against postal employees, predates the republic; its special agents (originally called surveyors) date back to 1772.4

The number of federal agencies and divisions within those agencies are too numerous to mention individually, and the number of federal police personnel has grown substantially since 9/11 and continues to grow. Still, compared to city, county, and state law enforcement, the number of federal officers is relatively low, and the competition for these positions is high. Federal positions also tend to require a bachelor’s degree. Therefore, most people interested in law enforcement careers will find employment at the state or local levels rather than at the federal level.

Organizational Structure

The quasi-military nature of police work includes a time-in-rank promotion system that typically requires officers to spend a prescribed amount of time at each rank before they can move up to the next level. A police officer, deputy sheriff, or state trooper who has the requisite experience in patrol (two to five years is common) and a clean record with the agency is ordinarily eligible to take a promotional exam for sergeant or detective. Promotional exams are also usually required for positions such as detective and criminal investigator, although these positions do not necessarily have supervisory duties or seniority over patrolmen.

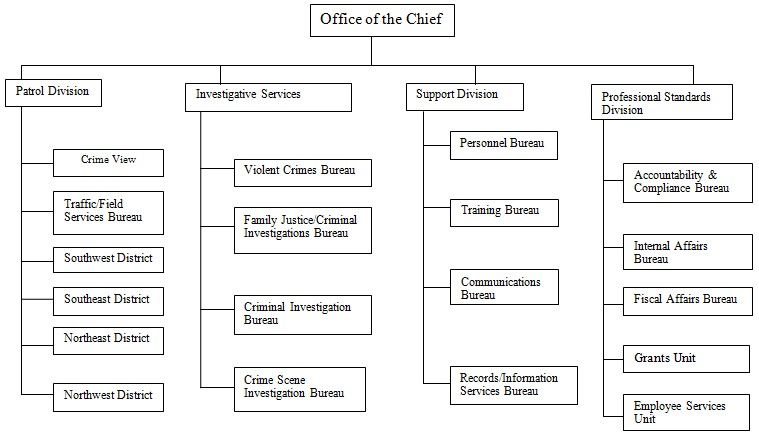

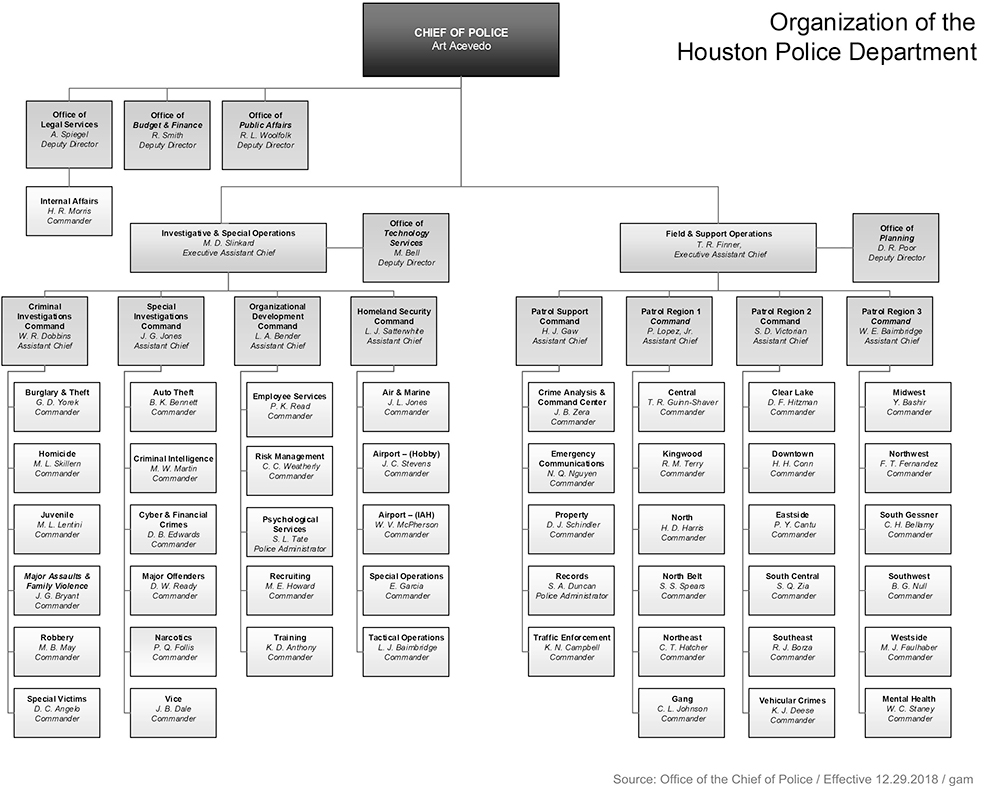

The seniority ladder and the types of promotional opportunities available will vary based on the size of the police department, as each division, unit, shift, and detail in a police organization will have one or more supervisors (at this level, commonly called assistant chief, director, or commander). You can see the difference in the organizational charts below. As a mid-size organization, the Fresno Police Department has four major divisions, while as a large organization, the Houston Police Department houses seven; in both organizations, divisions are comprised of multiple units, details, and commands.

Fresno Police Department Organizational Chart

The organizational chart for the Fresno Police Department is typical for police ranks in a mid-sized agency.

Image via Creative Commons.

Houston Police Department Organizational Chart

The organizational chart for a large metro police department like the Houston Police Department allows for more specialized branches, with more positions at the command level, compared to smaller PDs.

Image used with permission from the Houston Police Department.

The Promotions Process

In most police departments, promotions are based on seniority and a competitive exam process. These tests vary by department and agency. Some exams, such as that for sergeant or captain, are usually offered on a rolling basis. As candidates move up the ranks, exams to qualify for promotion to the next level are typically offered on a more limited basis. At all levels, study materials are generally made available to help prepare candidates.

It is not unusual for “study buddies” to get together to prepare for these exams. Even though they are competing against one another for a limited number of promotions, the camaraderie among officers often outweighs their competitiveness. Officers want their “brothers and sisters” in law to succeed and often help them to do so. Officers seeking promotion will also interview with superior officers and, based on their test and interview scores and an assessment of their work history, the agency will compile an eligibility roster and then promote based on each officer’s rank on the list.

Continue reading to learn more about promotional opportunities within the ranks.

Mid-Level Ranks

Detective

A detective is a full-time criminal investigator. Though most agencies base assignment to detective positions on time-in-rank and a promotional exam, making the transition from officer to detective a promotion in duties, it is not typically a supervisory position; in other words, except in limited circumstances, detectives cannot tell patrol officers what to do. Detectives have long been glamorized by Hollywood, and although investigating can be interesting work, a detective will spend a lot of time at his or her desk making telephone calls and conducting Internet and database searches, as well as writing reports and helping to prepare cases for court. A short list of a detective’s duties includes:

- Working with crime scene investigators to gather and catalog forensic evidence.

- Interviewing victims and witnesses and interrogating suspects (although “interview” and “interrogate” are often used interchangeably, their definitions in the context of the criminal law are distinct. In general, police interview victims and witnesses, and they interrogate suspects who are the focus of criminal investigations; this distinction has important legal ramifications.)

- Analyzing evidence, building cases, writing reports, and working with prosecutors to prepare cases for trial.

- Testifying in court when cases do not end in plea bargains.

- Keeping victims and witnesses informed of case status.

- Reviewing cold cases and following up on new leads.

Smaller agencies with lower volumes of crime do not always allow for investigative specialization. Their detectives may be generalists who investigate all types of crimes that occur in the jurisdiction, but in larger agencies, detectives tend to specialize in a particular category of crime.

Perhaps the most prestigious of these specializations is homicide. Homicide detectives are charged with investigating murders as well as aggravated assaults when it is likely that the victims will die. Homicide detectives also investigate suicides because these must be treated as homicides until evidence suggests otherwise. These detectives are usually seasoned veterans who have honed their investigative skills through many years of education, training, and experience and have generally proven themselves as investigators of other types of crime before moving up to homicides. Because of the seriousness of these crimes, homicide detectives have a greater role than other investigators in initial crime scene investigations. Their deliberate attention to detail is crucial to solving the most serious of crimes.

Crime Scene Investigator

Over the last several decades, criminal investigators, also known as crime scene investigators (or “criminalists”) have evolved as a specialty apart from regular detectives. In some agencies, these are full-fledged police officers who have received special training in criminalistics, but increasingly these are civilians with degrees in biology and/or chemistry and highly specialized training in processing crime scenes. Particularly important are the identification and proper handling of pieces of evidence, including hairs, fibers, fingerprints, and blood, that are often left behind at crime scenes. Often just a “trace” of this evidence is left behind, but even the smallest piece of evidence, particularly traces that can be analyzed for DNA, can be crucial to solving a case. This specialty has developed in recent years in conjunction with scientific advances that require expertise beyond that of regular police officers and detectives, so colleges and universities have created specialized degree programs to meet this need. People who are interested in this specialty should seek out degree programs in forensic science that combine criminal justice education with courses in the natural sciences.

Sergeant

A sergeant is a front-line supervisor who leads a group of officers assigned to a particular unit of the agency. Most sergeants start with patrol supervision, though other divisions do require sergeants. The sergeant is a “shirt sleeves” supervisor who typically performs the same work that his or her officers are required to do. As such, the job description is basically the same as that of an officer with added supervisory responsibilities. As leaders, sergeants strongly influence their officers’ approach to the job and are ultimately held accountable for many major decisions that take place in the field. In addition to patrol, some sergeants supervise specialized field units or civilian personnel at headquarters. Regardless of the assignment, sergeants take an active role in training, developing, and evaluating their employees.

Changing Community Relations

A recent survey from the Pew Research Center conducted by the National Police Research Platform interviewed nearly 8,000 police officers from departments with 100 officers or more. The survey, one of the largest of its kind, asked officers to discuss their attitudes towards their jobs and the public in light of the high-profile fatal incidents involving minority citizens that have taken place over the past few years, causing growing tensions between officers and the public. “Police work has always been hard. Today police say it is even harder,” the report explains. “Overall, more than eight-in-ten (86%) say police work is harder today as a result of these high-profile incidents.”

Higher Ranks

American law enforcement agencies borrow a great deal from the military, including the basic rank structure that exists in most agencies. After the rank of sergeant and detective, the next level up is lieutenant, and then captain. Up to this level, ranks are fairly consistent, but after captain, agencies begin to diverge. Some may continue with military ranks such as major and colonel, but others do not. It depends on how big the agency is and how “tall” its organizational structure happens to be. In the Houston Police Department, for example, the rank structure above captain is:

- Assistant Chief

- Executive Assistant Chief

- Chief

Each of the above ranks is an appointed position and, therefore, does not necessarily follow the same process that exists up to the rank of captain – namely, a formal time-in-rank promotional structure based on testing, interviews, and job history. As noted previously, most police officers must spend three to five years at that level before testing for sergeant or detective. Similarly, someone must hold the rank of sergeant or detective for one to three years, depending on the agency, before testing for lieutenant and then must hold that rank for another one to three years before taking the test for captain. The length of time required at each rank before becoming eligible to test for the next higher rank varies from agency to agency, but it is frequently a strict requirement. Note, though, that some agencies will waive a certain amount of experience for officers who hold an associate’s, bachelor’s, or master’s degree. Time spent waiting for a promotion can be difficult for some individuals, especially those with formal education and other strong credentials, but the tradeoff is that promotion is based on a more objective and less political process than exists in the private sector.

Chief of Police

The top rung of the ladder in a municipal police department is the rank of chief. In general, police chiefs are appointed by the mayor or city manager and approved by the city council, and they can be removed from the position by the same. However, in some departments, the head of the department is a civilian; for example, the New York Police Department (NYPD) is headed by a civilian with the title of “police commissioner.” Since the beginning of professional policing, the debate has raged about whether it is better to hire a chief from outside the agency or to promote from within, and there is no clear answer to that question. It depends on a number of variables. Agencies with a stated preference for promoting from within point to the need to reward proven and loyal employees, but other departments believe it is necessary to bring in “new blood” with a fresh perspective. An outsider is not committed to the status quo and is sometimes better able to identify areas in which the department can improve. Promoting from within is the more common preference, but even these agencies will sometimes go outside if circumstances warrant doing so, especially in the wake of a major scandal or pattern of corruption when reform is a top priority.

Sheriff

At the county level, the sheriff is usually an elected official. In fact, sheriffs are typically selected in partisan elections in which they are identified and supported by their political parties. Why are sheriffs partisan politicians? It is because of tradition and nothing more. This longstanding tradition is somewhat controversial because, in theory, under this process, the most important job qualification is popularity rather than experience or preparation for the job. With the exception of convicted felons, virtually anyone can become sheriff if he or she is able to get enough votes. History is full of examples of a county’s favorite son or war hero coming home and becoming sheriff, and some of these have had questionable qualifications.

That said, in actual practice, it is difficult for anyone without law enforcement experience to be elected sheriff. In some cases, sheriffs are experienced – perhaps even retired – municipal police officers or supervisors, and it is not uncommon for a sheriff to have been a ranking deputy from within the same office. In any case, the political component is the primary difference (aside from jurisdiction) between a city police chief and a county sheriff. Some counties have created county police departments to combine typical municipal law enforcement duties with the traditional duties of sheriffs’ offices, but this is an exception to the rule.

Federal Top Ranks

Each federal police agency has its own structure, and though some of these may overlap, it cannot be taken as a given that the rank structure in one federal agency will be similar to that of another. However, these agencies do as a general rule follow the military-type rank structure for civilian police, with a few differences. For example, in some agencies, such as the Defense Logistics Agency Police, the police division will report to a director, rather than a chief.

Police Officer Salary and Career Outlook

The number of police and detectives is expected to grow 5% in the decade between 2019 and 2029.5 While this rate of growth is slower than the average for all occupations, it translates to over 40,000 additional jobs; in addition, these numbers do not take into account the number of positions that will be available due to retirements.5 Police agencies added many new officers in the 80s and 90s, and these officers are now eligible for retirement. This is happening in departments all across the country, and this indicates that qualified young men and women who hope to begin law enforcement careers in the near future should be able to find work.

Although some governments face intense pressure to cut their budgets and police layoffs are not unheard of, the loss of police jobs is rarely supported by the citizens who expect service and protection from those officers. All things considered, for the foreseeable future, the job outlook for police officers should remain bright. For example, in Chicago, 1,358 new entry-level officers were graduated from the police academy between January 2018 and April 2019, and the department continues to accept applications for the entry-level police entrance exam.9

The average pay for police and sheriff’s patrol officers, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, is $67,600 per year, or $32.50 per hour.7 California police officers are paid the highest salaries, with an average wage reported of $105,220, followed by Alaska cops at $87,870 and New Jersey police officers at $86,840.7 However, the average salary is not the only factor that makes a state a good one to work as a police officer; other factors to consider are property prices, the cost of living, projected employment of officers, and the projected growth rate for cops. To find out more, check out our Police Officer Salary Index and Outlook by State table, with a comprehensive ranking of the best states to be a police officer.

The state of California is home to the largest number of cops, with an estimated 72,380.7 The state of Texas has the second-largest number of police officers (58,840) and New York comes in third (55,590).7 To find law enforcement jobs in your area, check out our Police Jobs page.

Law Enforcement Shortages

“…most police (86%) say their department does not have enough officers to adequately police the community. Police who work in larger agencies (with 1,000 officers of more) are more likely than those working in smaller agencies to say that there is a shortage of officers in their department (95% vs. 79%).”

-Pew Research Center, “Behind the Badge”

Frequently Asked Questions

What do police officers do?

Police officers perform a wide variety of tasks. As a law enforcement officer, you can expect to patrol by car and on foot, investigate crime scenes, respond to emergency and non-emergency calls, respond to traffic incidents and violations, write reports, and be present to control crowds and escort funeral processions. These are only a few of the tasks that you will be responsible for as an officer of the law. You should be prepared to go above and beyond your assigned duties as a cop.

How much do cops make?

The average US salary for police officers and sheriff’s patrol officers is $67,600.7 Entry-level officers will likely make significantly less than this amount on average, but can usually count on graduated pay increases based on time-in-rank promotions. Read more about police salaries on our Police Officer Salaries page.

What kind of education do I need to start a police officer career?

The education requirements to become a police officer vary widely among departments. Most police officer jobs require a minimum of a high school diploma or GED, but others require a two- or four-year degree. Refer to our Police Officer Education page or check the department(s) in your area to find out specific requirements.

How do I get hired as a SWAT, K9, dive team officer, or another type of specialty?

In order to work on a special unit, you must be hired and work as a patrol officer for a certain period of time; one year is common, but many departments require additional experience. Once you have built the required experience in patrol, you can apply for special unit positions. Note that even departments that accept lateral applications for patrol officers (that is, applications from officers who are currently certified and working with another department) usually do not accept lateral applications for specialized teams, so it’s best to plan your career with this in mind.

Is it worth it to start a career in law enforcement?

The answer to this question is up to the individual, but a career in law enforcement can certainly be a solid job path with plenty of opportunities for advancement, providing job security and personal satisfaction through serving others. If you are considering entering a career in law enforcement, you should read more about becoming a police officer and seek expert advice from others who have worked in the field.

Police Pride

“A majority of all officers say their work in law enforcement nearly always (23%) or often (35%) makes them feel proud. About half say their work nearly always (10%) or often (41%) makes them feel frustrated.” -Pew Research Center, Behind the Badge

Additional Resources

- Arrested Development – A book by the former police chief of the Madison Police Department (Wisconsin), David C. Couper, discussing police subculture and how to overcome common obstacles to improve policing.

- Behind the Badge – A Pew Research Center national survey and analysis that discusses the recent challenges and tensions in policing.

This guide was written in part by William Prince, Adjunct Instructor of Criminal Justice at Wharton County Junior College.

References:

1. Gaines, L.K., & Miller, R.L. (2013). CJ2. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. p. 102.

2. Many variations of this popular saying exist, and its precise origin is unknown.

3. Texas Department of Public Safety: https://www.dps.texas.gov/

4. US Postal Inspection Service, A Chronology of the United States Postal Inspection Service: https://www.uspis.gov/about/history-of-uspis

5. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2019 Occupational Outlook Handbook, Police and Detectives: https://www.bls.gov/ooh/Protective-Service/Police-and-detectives.htm

6. Chicago Sun-Times, “Application process open for another police exam; Rahm, Johnson tout crime stats.” 1 Apr. 2019: https://chicago.suntimes.com/2019/4/1/18482487/application-process-open-for-another-police-exam-rahm-johnson-tout-crime-stats/

7. Bureau of Labor Statistics, May 2019 Occupational and Employment Wages, Police and Sheriff’s Patrol Officers: https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes333051.htm

8. O*NET OnLine, Police Patrol Officers: https://www.onetonline.org/link/summary/33-3051.00